Projects

In the early stages of a project, you’re experimenting with new ideas and making decisions based on what you want. As your project increases in popularity, you’ll find yourself working with your users and contributors more.

Maintaining a project requires more than code. These tasks are often unexpected, but they’re just as important to a growing project. We’ve gathered a few ways to make your life easier, from documenting processes to leveraging your community.

Documenting your processes

Writing things down is one of the most important things you can do as a maintainer.

Documentation not only clarifies your own thinking, but it helps other people understand what you need or expect, before they even ask.

Writing things down makes it easier to say no when something doesn’t fit into your scope. It also makes it easier for people to pitch in and help. You never know who might be reading or using your project.

Even if you don’t use full paragraphs, jotting down bullet points is better than not writing at all.

Remember to keep your documentation up-to-date. If you’re not able to always do this, delete your outdated documentation or indicate it is outdated so contributors know updates are welcome.

Write down your project’s vision

Start by writing down the goals of your project. Add them to your README, or create a separate file called VISION. If there are other artifacts that could help, like a project roadmap, make those public as well.

Having a clear, documented vision keeps you focused and helps you avoid “scope creep” from others’ contributions.

For example, @lord discovered that having a project vision helped him figure out which requests to spend time on. As a new maintainer, he regretted not sticking to his project’s scope when he got his first feature request for Slate.

I fumbled it. I didn’t put in the effort to come up with a complete solution. Instead of a half-assed solution, I wish I had said “I don’t have time for this right now, but I’ll add it to the long term nice-to-have list.”

— @lord, “Tips for new open source maintainers”

Communicate your expectations

Rules can be nerve-wracking to write down. Sometimes you might feel like you’re policing other people’s behavior or killing all the fun.

Written and enforced fairly, however, good rules empower maintainers. They prevent you from getting dragged into doing things you don’t want to do.

Most people who come across your project don’t know anything about you or your circumstances. They may assume you get paid to work on it, especially if it’s something they regularly use and depend on. Maybe at one point you put a lot of time into your project, but now you’re busy with a new job or family member.

All of this is perfectly okay! Just make sure other people know about it.

If maintaining your project is part-time or purely volunteered, be honest about how much time you have. This is not the same as how much time you think the project requires, or how much time others want you to spend.

Here are a few rules that are worth writing down:

How a contribution is reviewed and accepted (Do they need tests? An issue template?)

The types of contributions you’ll accept (Do you only want help with a certain part of your code?)

When it’s appropriate to follow up (for example, “You can expect a response from a maintainer within 7 days. If you haven’t heard anything by then, feel free to ping the thread.”)

How much time you spend on the project (for example, “We only spend about 5 hours per week on this project”)

Jekyll, CocoaPods, and Homebrew are several examples of projects with ground rules for maintainers and contributors.

Keep communication public

Don’t forget to document your interactions, too. Wherever you can, keep communication about your project public. If somebody tries to contact you privately to discuss a feature request or support need, politely direct them to a public communication channel, such as a mailing list or issue tracker.

If you meet with other maintainers, or make a major decision in private, document these conversations in public, even if it’s just posting your notes.

That way, anybody who joins your community will have access to the same information as someone who’s been there for years.

Learning to say no

You’ve written things down. Ideally, everybody would read your documentation, but in reality, you’ll have to remind others that this knowledge exists.

Having everything written down, however, helps depersonalize situations when you do need to enforce your rules.

Saying no isn’t fun, but “Your contribution doesn’t match this project’s criteria” feels less personal than “I don’t like your contribution”.

Saying no applies to many situations you’ll come across as a maintainer: feature requests that don’t fit the scope, someone derailing a discussion, doing unnecessary work for others.

Keep the conversation friendly

One of the most important places you’ll practice saying no is on your issue and pull request queue. As a project maintainer, you’ll inevitably receive suggestions that you don’t want to accept.

Maybe the contribution changes your project’s scope or doesn’t match your vision. Maybe the idea is good, but the implementation is poor.

Regardless of the reason, it is possible to tactfully handle contributions that don’t meet your project’s standards.

If you receive a contribution you don’t want to accept, your first reaction might be to ignore it or pretend you didn’t see it. Doing so could hurt the other person’s feelings and even demotivate other potential contributors in your community.

The key to handling support for large-scale open source projects is to keep issues moving. Try to avoid having issues stall. If you’re an iOS developer you know how frustrating it can be to submit radars. You might hear back 2 years later, and are told to try again with the latest version of iOS.

— @KrauseFx, “Scaling open source communities”

Don’t leave an unwanted contribution open because you feel guilty or want to be nice. Over time, your unanswered issues and PRs will make working on your project feel that much more stressful and intimidating.

It’s better to immediately close the contributions you know you don’t want to accept. If your project already suffers from a large backlog, @steveklabnik has suggestions for how to triage issues efficiently.

Secondly, ignoring contributions sends a negative signal to your community. Contributing to a project can be intimidating, especially if it’s someone’s first time. Even if you don’t accept their contribution, acknowledge the person behind it and thank them for their interest. It’s a big compliment!

If you don’t want to accept a contribution:

Thank them for their contribution

Explain why it doesn’t fit into the scope of the project, and offer clear suggestions for improvement, if you’re able. Be kind, but firm.

Link to relevant documentation, if you have it. If you notice repeated requests for things you don’t want to accept, add them into your documentation to avoid repeating yourself.

Close the request

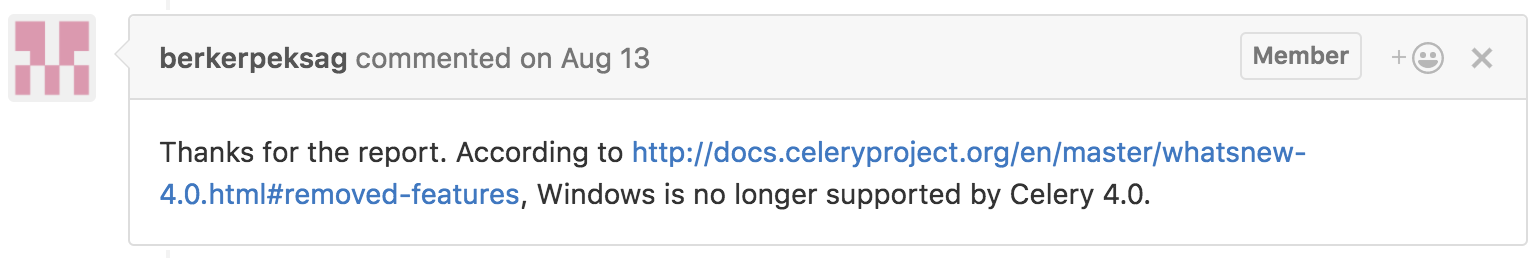

You shouldn’t need more than 1-2 sentences to respond. For example, when a user of celery reported a Windows-related error, @berkerpeksag responded with:

If the thought of saying no terrifies you, you’re not alone. As @jessfraz put it:

I’ve talked to maintainers from several different open source projects, Mesos, Kubernetes, Chromium, and they all agree one of the hardest parts of being a maintainer is saying “No” to patches you don’t want.

Don’t feel guilty about not wanting to accept someone’s contribution. The first rule of open source, according to @shykes: “No is temporary, yes is forever.” While empathizing with another person’s enthusiasm is a good thing, rejecting a contribution is not the same as rejecting the person behind it.

Ultimately, if a contribution isn’t good enough, you’re under no obligation to accept it. Be kind and responsive when people contribute to your project, but only accept changes that you truly believe will make your project better. The more often you practice saying no, the easier it becomes. Promise.

Be proactive

To reduce the volume of unwanted contributions in the first place, explain your project’s process for submitting and accepting contributions in your contributing guide.

If you’re receiving too many low-quality contributions, require that contributors do a bit of work beforehand, for example:

Fill out a issue or PR template/checklist

Open an issue before submitting a PR

If they don’t follow your rules, close the issue immediately and point to your documentation.

While this approach may feel unkind at first, being proactive is actually good for both parties. It reduces the chance that someone will put in many wasted hours of work into a pull request that you aren’t going to accept. And it makes your workload easier to manage.

Ideally, explain to them and in a CONTRIBUTING.md file how they can get a better indication in the future on what would or would not be accepted before they begin the work.

— @MikeMcQuaid, “Kindly Closing Pull Requests”

Sometimes, when you say no, your potential contributor may get upset or criticize your decision. If their behavior becomes hostile, take steps to defuse the situation or even remove them from your community, if they’re not willing to collaborate constructively.

Embrace mentorship

Maybe someone in your community regularly submits contributions that don’t meet your project’s standards. It can be frustrating for both parties to repeatedly go through rejections.

If you see that someone is enthusiastic about your project, but needs a bit of polish, be patient. Explain clearly in each situation why their contributions don’t meet the expectations of the project. Try pointing them to an easier or less ambiguous task, like an issue marked “good first issue,” to get their feet wet. If you have time, consider mentoring them through their first contribution, or find someone else in your community who might be willing to mentor them.

Leverage your community

You don’t have to do everything yourself. Your project’s community exists for a reason! Even if you don’t yet have an active contributor community, if you have a lot of users, put them to work.

Share the workload

If you’re looking for others to pitch in, start by asking around.

One way to gain new contributors is to explicitly label issues that are simple enough for beginners to tackle. GitHub will then surface these issues in various places on the platform, increasing their visibility.

When you see new contributors making repeated contributions, recognize their work by offering more responsibility. Document how others can grow into leadership roles if they wish.

Encouraging others to share ownership of the project can greatly reduce your own workload, as @lmccart discovered on her project, p5.js.

I’d been saying, “Yeah, anyone can be involved, you don’t have to have a lot of coding expertise […].” We had people sign up to come [to an event] and that’s when I was really wondering: is this true, what I’ve been saying? There are gonna be 40 people who show up, and it’s not like I can sit with each of them…But people came together, and it just sort of worked. As soon as one person got it, they could teach their neighbor.

— @lmccart, “What Does “Open Source” Even Mean? p5.js Edition”

If you need to step away from your project, either on hiatus or permanently, there’s no shame in asking someone else to take over for you.

If other people are enthusiastic about its direction, give them commit access or formally hand over control to someone else. If someone forked your project and is actively maintaining it elsewhere, consider linking to the fork from your original project. It’s great that so many people want your project to live on!

@progrium found that documenting the vision for his project, Dokku, helped those goals live on even after he stepped away from the project:

I wrote a wiki page describing what I wanted and why I wanted it. For some reason it came as a surprise to me that the maintainers started moving the project in that direction! Did it happen exactly how I’d do it? Not always. But it still brought the project closer to what I wrote down.

Let others build the solutions they need

If a potential contributor has a different opinion on what your project should do, you may want to gently encourage them to work on their own fork.

Forking a project doesn’t have to be a bad thing. Being able to copy and modify projects is one of the best things about open source. Encouraging your community members to work on their own fork can provide the creative outlet they need, without conflicting with your project’s vision.

I cater to the 80% use case. If you are one of the unicorns, please fork my work. I won’t get offended! My public projects are almost always meant to solve the most common problems; I try to make it easy to go deeper by either forking my work or extending it.

— @geerlingguy, “Why I Close PRs”

The same applies to a user who really wants a solution that you simply don’t have the bandwidth to build. Offering APIs and customization hooks can help others meet their own needs, without having to modify the source directly. @orta found that encouraging plugins for CocoaPods led to “some of the most interesting ideas”:

It’s almost inevitable that once a project becomes big, maintainers have to become a lot more conservative about how they introduce new code. You become good at saying “no”, but a lot of people have legitimate needs. So, instead you end up converting your tool into a platform.

Bring in the robots

Just as there are tasks that other people can help you with, there are also tasks that no human should ever have to do. Robots are your friend. Use them to make your life as a maintainer easier.

Require tests and other checks to improve the quality of your code

One of the most important ways you can automate your project is by adding tests.

Tests help contributors feel confident that they won’t break anything. They also make it easier for you to review and accept contributions quickly. The more responsive you are, the more engaged your community can be.

Set up automatic tests that will run on all incoming contributions, and ensure that your tests can easily be run locally by contributors. Require that all code contributions pass your tests before they can be submitted. You’ll help set a minimum standard of quality for all submissions. Required status checks on GitHub can help ensure no change gets merged without your tests passing.

If you add tests, make sure to explain how they work in your CONTRIBUTING file.

I believe that tests are necessary for all code that people work on. If the code was fully and perfectly correct, it wouldn’t need changes – we only write code when something is wrong, whether that’s “It crashes” or “It lacks such-and-such a feature”. And regardless of the changes you’re making, tests are essential for catching any regressions you might accidentally introduce.

— @edunham, “Rust’s Community Automation”

Use tools to automate basic maintenance tasks

The good news about maintaining a popular project is that other maintainers have probably faced similar issues and built a solution for them.

There are a variety of tools available to help automate some aspects of maintenance work. A few examples:

semantic-release automates your releases

mention-bot mentions potential reviewers for pull requests

Danger helps automate code review

no-response closes issues where the author hasn’t responded to a request for more information

dependabot-preview checks your dependency files every day for outdated requirements and opens individual pull requests for any it finds

For bug reports and other common contributions, GitHub has Issue Templates and Pull Request Templates, which you can create to streamline the communication you receive. @TalAter made a Choose Your Own Adventure guide to help you write your issue and PR templates.

To manage your email notifications, you can set up email filters to organize by priority.

If you want to get a little more advanced, style guides and linters can standardize project contributions and make them easier to review and accept.

However, if your standards are too complicated, they can increase the barriers to contribution. Make sure you’re only adding enough rules to make everyone’s lives easier.

If you’re not sure which tools to use, look at what other popular projects do, especially those in your ecosystem. For example, what does the contribution process look like for other Node modules? Using similar tools and approaches will also make your process more familiar to your target contributors.

It’s okay to hit pause

Open source work once brought you joy. Maybe now it’s starting to make you feel avoidant or guilty.

Perhaps you’re feeling overwhelmed or a growing sense of dread when you think about your projects. And meanwhile, the issues and pull requests pile up.

Burnout is a real and pervasive issue in open source work, especially among maintainers. As a maintainer, your happiness is a non-negotiable requirement for the survival of any open source project.

Although it should go without saying, take a break! You shouldn’t have to wait until you feel burned out to take a vacation. @brettcannon, a Python core developer, decided to take a month-long vacation after 14 years of volunteer OSS work.

Just like any other type of work, taking regular breaks will keep you refreshed, happy, and excited about your work.

In maintaining WP-CLI, I’ve discovered I need to make myself happy first, and set clear boundaries on my involvement. The best balance I’ve found is 2-5 hours per week, as a part of my normal work schedule. This keeps my involvement a passion, and from feeling too much like work. Because I prioritize the issues I’m working on, I can make regular progress on what I think is most important.

— @danielbachhuber, “My condolences, you’re now the maintainer of a popular open source project”

Sometimes, it can be hard to take a break from open source work when it feels like everybody needs you. People may even try to make you feel guilty for stepping away.

Do your best to find support for your users and community while you’re away from a project. If you can’t find the support you need, take a break anyway. Be sure to communicate when you’re not available, so people aren’t confused by your lack of responsiveness.

Taking breaks applies to more than just vacations, too. If you don’t want to do open source work on weekends, or during work hours, communicate those expectations to others, so they know not to bother you.

Take care of yourself first!

Maintaining a popular project requires different skills than the earlier stages of growth, but it’s no less rewarding. As a maintainer, you’ll practice leadership and personal skills on a level that few people get to experience. While it’s not always easy to manage, setting clear boundaries and only taking on what you’re comfortable with will help you stay happy, refreshed, and productive.

Last updated